Second Best Quote of the Year

Preach on Kanye. And Happy New Years, folks.

A humble movie diary from a guy with too much time on his hands and too much randomness on his brain. Thanks for the title Cam.

there is again a lot of gesture toward Theme in his character, but absolutely no narrative payoff. Yes, I get it. Jack Black/Martin Sheen/Heart of Darkness. Show me, don't tell me. I suspect that Jackson is a great director. I fear that he's on the verge of pomposity, the pulp heart that drove Dead Alive and The Frighteners and even to some degree Heavenly Creatures, extracted from his chest by the sheer ambition of the LOTR flicks and the Oscar-driven desire to be Important.

there is again a lot of gesture toward Theme in his character, but absolutely no narrative payoff. Yes, I get it. Jack Black/Martin Sheen/Heart of Darkness. Show me, don't tell me. I suspect that Jackson is a great director. I fear that he's on the verge of pomposity, the pulp heart that drove Dead Alive and The Frighteners and even to some degree Heavenly Creatures, extracted from his chest by the sheer ambition of the LOTR flicks and the Oscar-driven desire to be Important.

Actually, that's not fair. There's plenty of evidence that the pulp heart is willing in Kong. See the aforementioned T. Rex/Kong fight scene (which also pays off beautifully in the XBox 360 game. Thanks Evan!). See the ice-skating monkey scene. See the sheer go-for-broke racist brilliance of the scenes with the savages--credit Jackson for the insight that "hey, it won't work unless we make it as Birth of a Nation as possible," even after the drumbeats of criticism (if you'll pardon a turn of phrase) following the accusations of racist iconography of the Orcs vs. the Aryans.

Or even moreso, the sheer go-for-broke love affair between Naomi Watts and the Monkey. All Haters, disembark here. Naomi has It, whether it's macking on Chad Everett in Mullholland Drive, working her tortured soul in 21 Grams, or just being luminous. She's stylish, vulnerable, and surprising. She's able to make left turns in character seem revelatory and complicating, rather than inconsistent. Unlike many people, I liked most of the first act (post-Theme montage), because it sets you up to understand how this woman comes to love this monkey--she's been betrayed and victimized her whole life, just when she is opening up to her dreams and most needs protection. Here comes the Ultimate Warrior, primed to give her that protection, and then what happens--she moves from victim to victimizer, becoming the unwitting agent of his betrayal. That's Shakespearean, bitches.

And Jackson feels it, plays the relationship on a sheer emotional chord, without worrying about Themes, or Importance, or other cloudy abstractions.

And thinking about how well the pulp primitivism worked in this film, and how poorly the gestures toward theme worked, got me into why I dug this film so much ultimately. King Kong is Peter Jackson's 8 1/2, or his Life Aquatic. It captures a filmmaker reflecting on himself, looking with both joy and dismay at both his showmanship heart and his belief that he has something else stirring, Something to Say. Or worse, requires Something to Say as penance for the desire to thrill/shock/awe us. It's the last temptation of Peter Jackson, to see if he feels he needs to justify his existence by moving from his Jaws and Indiana Jones phase into his Amistad/Color Purple phase. Or god forbid, his Beloved phase. Isn't it interesting how we see this happen over and over again to directors, even though we keep telling them that they had it right the first time?

This is a meditation for another time, however. King Kong is great, and underperforming slightly at the box office, because for whatever reasons movies about the directors tend to do that kind of thing (see Life Aquatic, Vertigo, etc.). I suspect it is a movie that will only be appreciated as more than a remake much later. We are watching a man put his dreams up on to the screen. Better yet, we are watching him at the phase in his life when he's just been given the keys to the Chocolate Factory, and confronting the question of 'what happened to the boy who got everything he ever wanted?'

God help us, if those dreams look too much like The Lovely Bones and not enough like Halo.

Next Time: Alone in the Dark

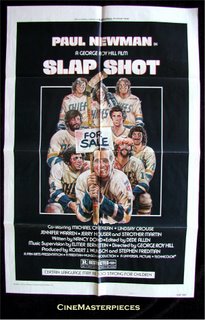

I was watching Slap Shot for maybe the billionth time the other day with Frank, Dan, and Irene. The occasion was supposed to be inauguration of Irene into the cult of the Hanson brothers. But for whatever reason--maybe it was the repetitive viewings, maybe it was the sluggishness brought on by the fatal combination of hangover and chicken and waffles, maybe it was just kismet--I found myself locked onto Paul Newman.

I was watching Slap Shot for maybe the billionth time the other day with Frank, Dan, and Irene. The occasion was supposed to be inauguration of Irene into the cult of the Hanson brothers. But for whatever reason--maybe it was the repetitive viewings, maybe it was the sluggishness brought on by the fatal combination of hangover and chicken and waffles, maybe it was just kismet--I found myself locked onto Paul Newman. But there is something special about Newman. He is not primarily remembered as an asshole. As Dan pointed out, Newman is kind of an awful human being in Hud. But you still kind of understand why the kid would want to emulate him. Cool Hand Luke? Awesomely cool. And...asshole. And on and on--The Hustler, The Sting, The Verdict...

But there is something special about Newman. He is not primarily remembered as an asshole. As Dan pointed out, Newman is kind of an awful human being in Hud. But you still kind of understand why the kid would want to emulate him. Cool Hand Luke? Awesomely cool. And...asshole. And on and on--The Hustler, The Sting, The Verdict...

But I digress.

But I digress.