The Accidental Anarchist

But just because there is a formula, does not mean there cannot be innovation. Shakespeare wrote a whole lot of sonnets with a set structure. And let’s not get started on haiku. Or, consider the case of Pierce Brosnan. Brosnan has been a generally successful Bond. However, Brosnan’s best work has involved giving the piss to the Bond franchise. Remington Steele was a thinly veiled Bond joke, providing us with the suave, roguish British enigma who is secretly so incompetent at everything but conning people that Stephanie Zimbalist looks like Jack Bauer next to him. The early years of the show are amazing romantic comedy, so much so that the Bond producers (missing the joke?) offered him the Bond gig.

Even within the Bond set, there is an element of subversion to Brosnan’s performance, particularly in the best of his run, Tomorow Neverf Dies, which I believe features his defining moment as Bond. During a routine Bond movie stunt, Brosnan is steering a car by remote control from the back seat, and manages to do the usual Bondian con that results in the bad guys taking themselves out. But then, Brosnan breaks into a boyish laugh at his own cleverness. It’s a defining moment for his version of Bond—distinct from Connery’s cold machismo, Moore’s ironic detachment, Dalton’s angry solemnity, and Lazenby’s…blandness? There’s a very real sense that Brosnan plays Bond as being just as surprised as what he gets away with as we are, but only able to show that delight and surprise in private—behind the suave mask, he’s a little less cold, a little more relatable.

However, despite evidence that the formula was working (nice bump in Bond receipts, nice ratings for Remington Steele), the Powers That Be fucked with things. In Remington Steele, they started to explore the back story, started to make Brosnan a little more competent. (Maybe this was a Brosnan call—it is rather emasculating to play the romantic equivalent of Inspector Gadget). And the Powers That Be in charge of the Bond franchise decided to innovate the franchise not by playing to what has been successful (letting a solid performer innovate within the formula) but instead by doing what has sunk each performer (“updating” the formula with darkening plots such as the James Bond-gone-rogue bits, or strengthening the female characters and pretending that it has always been a great honor to be a Bond girl. It sure did wonders for Tanya Roberts and Maud Adams, right? Right?).

However, despite evidence that the formula was working (nice bump in Bond receipts, nice ratings for Remington Steele), the Powers That Be fucked with things. In Remington Steele, they started to explore the back story, started to make Brosnan a little more competent. (Maybe this was a Brosnan call—it is rather emasculating to play the romantic equivalent of Inspector Gadget). And the Powers That Be in charge of the Bond franchise decided to innovate the franchise not by playing to what has been successful (letting a solid performer innovate within the formula) but instead by doing what has sunk each performer (“updating” the formula with darkening plots such as the James Bond-gone-rogue bits, or strengthening the female characters and pretending that it has always been a great honor to be a Bond girl. It sure did wonders for Tanya Roberts and Maud Adams, right? Right?).

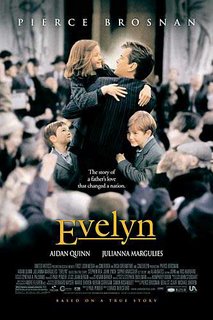

In other words, the formula conformed to what the audience expected (or more precisely, what the audience was perceived to expect), versus capitalizing on what the actor might bring to the table that was new and different and interesting.And now comes The Matador, Brosnan’s first important role since his official exit/discharge from the Bond franchise. The movie itself is fairly average—the typical hit man meets ordinary guy and both lives are changed independent movie set-up of the last few years. Kinnear (a decent actor) and Davis (a great actress who has done more with less) are stuck in hoplelessly didactic roles, maybe a notch above narrators.

What’s sad about The Matador is the movie fails to follow the actor to his logical conclusion, instead opting for something warmer and fuzzier. Like many of the post-Tarantino indie films in the mid-90s: the family is clearly rejuvenated by their partial adoption of Julian Noble and the introduction of bloody violence into the family, but nobody follows that to its natural conclusion. Is Brosnan’s manchild a new son for them, someone for them to take care of? What about the flirtation that Brosnan engages in with Davis (which essentially gets mentioned and dropped, despite the intriguing and queasy possibilities)? What about Kinnear’s clear mancrush on Brosnan, and the intriguing and queasy possibilities of that? What about the suggestion that Brosnan keeps his propensity to violence? Instead, the movie becomes: do Noble’s panic attacks get resolved? In other words, they take a damaged, vulnerable, self-satisfied guy and make him more competent, more conventional, more emo. More like us.

What’s sad about The Matador is the movie fails to follow the actor to his logical conclusion, instead opting for something warmer and fuzzier. Like many of the post-Tarantino indie films in the mid-90s: the family is clearly rejuvenated by their partial adoption of Julian Noble and the introduction of bloody violence into the family, but nobody follows that to its natural conclusion. Is Brosnan’s manchild a new son for them, someone for them to take care of? What about the flirtation that Brosnan engages in with Davis (which essentially gets mentioned and dropped, despite the intriguing and queasy possibilities)? What about Kinnear’s clear mancrush on Brosnan, and the intriguing and queasy possibilities of that? What about the suggestion that Brosnan keeps his propensity to violence? Instead, the movie becomes: do Noble’s panic attacks get resolved? In other words, they take a damaged, vulnerable, self-satisfied guy and make him more competent, more conventional, more emo. More like us.

Depressing, isn’t it.

Sure, Noble’s a mess, but Brosnan makes him a compelling mess, and frankly watching him start to give a substantial shit (as opposed to the mild cases of giving-a-shit that bring on his drinking and whoring binges and drunken apologies) is boring. The world needs a little anarchy, and watching Brosnan bring that kind of structured anarchy to the table is a rare pleasure. Sometimes, we don’t want to see growth, or change. Sometimes, we just want to see bad people do what they do, and get a little vicarious thrill. And is that so wrong?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home