'Johnny Utah IS Hot.'

That's all I have to say about Point Break. Now we're going to talk about Point Break Live. Point Break Live is a fairly straight telling of the saga of Johnny Utah, ex football great, now FBI agent, out to track down a devious group of bank robbers called the Ex Presidents.

That's all I have to say about Point Break. Now we're going to talk about Point Break Live. Point Break Live is a fairly straight telling of the saga of Johnny Utah, ex football great, now FBI agent, out to track down a devious group of bank robbers called the Ex Presidents. Kicked to the side by the F.B.I. brass ('cos that's the way shit goes down in the 80s), Utah is taken under the wing of another misfit, who has a name, but is, let's face it, Academy Award Winner Gary Busey.

Kicked to the side by the F.B.I. brass ('cos that's the way shit goes down in the 80s), Utah is taken under the wing of another misfit, who has a name, but is, let's face it, Academy Award Winner Gary Busey. Anyway, Busey has this Crazy Idea that the bank robbers might be surfers. So he sends Johnny undercover. You know, because great football players with bum knees make great surfers.

Anyway, Busey has this Crazy Idea that the bank robbers might be surfers. So he sends Johnny undercover. You know, because great football players with bum knees make great surfers.

Until Johnny is recruited by Bodhi, a zen master of what it means to lead the life free of fear. A life of 100% pure adrenaline.

Until Johnny is recruited by Bodhi, a zen master of what it means to lead the life free of fear. A life of 100% pure adrenaline. Ultimately, Johnny finds his loyalties divided between the straitlaced stuck up assholery of the F.B.I. and the intense, dangerous surfers.

Ultimately, Johnny finds his loyalties divided between the straitlaced stuck up assholery of the F.B.I. and the intense, dangerous surfers. Ultimately, however, the surfers reveal that they ARE the Ex Presidents, and that, as always, when in doubt we should listen to Busey. However, Johnny's cover is also blown. Violence ensues, innocents get hurt

Ultimately, however, the surfers reveal that they ARE the Ex Presidents, and that, as always, when in doubt we should listen to Busey. However, Johnny's cover is also blown. Violence ensues, innocents get hurt And Johnny has to take Bodhi down. In the most dramatic scene of the movie/play, Bodhi attempts to escape by skydiving, and Johnny chases him down. Without a parachute. Because that's how Keanu rolls, mother fucker.

And Johnny has to take Bodhi down. In the most dramatic scene of the movie/play, Bodhi attempts to escape by skydiving, and Johnny chases him down. Without a parachute. Because that's how Keanu rolls, mother fucker.

But Bodhi gets away.

But Bodhi gets away. Johnny chases Bodhi around the world, finally catching him in Australia during the 50 year storm, which brings it with the hardcore waves.

Johnny chases Bodhi around the world, finally catching him in Australia during the 50 year storm, which brings it with the hardcore waves. They fight, and Johnny gets the better of Bodhi, but then lets him go, sacrificing him to the storm. Again, that's how Keanu rolls.

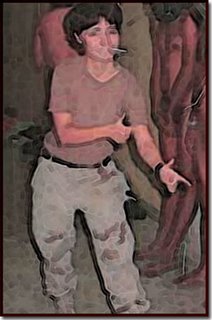

They fight, and Johnny gets the better of Bodhi, but then lets him go, sacrificing him to the storm. Again, that's how Keanu rolls.Despite my multiple Keanu references, you've probably figured out that isn't Keanu in the pictures. Overcoming performance anxiety, Julie decided to bring it with her Keanu impression and win over the crowd.

Now, the Keanu impression is an underrated art. It's almost surfer, but dumb instead of Zen/stoned. It's almost dumb, but with an edge of something that you can almost pretend is smarter than what it is. Now, you really have to appreciate the degree of difficulty here. First, it's not like Julie was rehearsing or anything. Her basic directions were 'read the cue cards' and 'if we push you over, go limp.' Maintaining The Keanu Voice the entire time, whether she was taking major bumps while being taught how to surf, being tackled by the big breasted production assistant with a massive sleeping bag (I've had dreams like that), or robbing a bank with cap guns and NO RUBBER MASK.

And how did she do?

A star is born.

Despite catcalling from the audience in appreciation of her fine work, and a proliferation of douchebags in the corner who looked like they were living the whole "we're the pretty boy jock fraternity from every 80s movie (sans Billy Zabka)," it was pretty remarkable what they were able to pull off in the performance space, including two kick ass skydiving scenes.

So What Did I Learn from All This?

1. I have a new pick for which of my friends is best equipped to be an action star. (sorry Danny)

2. You gotta live to get radical.

3. It's really kinda hot to watch a beautiful woman simulate bank robbery and sky diving. And sell meatball sandwiches.

Next Time: Roadhouse: The Musical